Washington Post: Repair Teams Try to Calm ‘Computer Rage’

Technicians Make House Calls to Fix Stubborn Equipment

By Ariana Eunjung Cha

Washington Post Staff Writer

Sunday, May 1, 2005;

NOVATO, Calif. — The young woman at the other end of the phone wept to Kelly Chessen that the world was against her. She had been in a minor car accident. A thief had stolen some things from her house. And now this: The family’s computer, which contained her husband’s business files, was dead.

Chessen, a crisis counselor who answered the hotline, soothingly assured the caller that such things happen to everyone, that it was no one’s fault, that her luck would turn around. It wasn’t until 20 minutes into the conversation that Chessen began to address the cause of the young woman’s agony. Send us the machine, Chessen said, and we’ll do everything we can to help.

Chessen, who once was a manager for a suicide prevention hotline, now works in customer service for DriveSavers Data Recovery Inc. “This is a lot like my old job,” she said. “Oftentimes the most helpful thing we can do is just to listen and to let people get whatever they are feeling off their chests.”

Technology has become a bane of modern life. People juggle a mountain of electronic equipment to store their most important records and intimate secrets. But the complicated nature of their machines, with their manuals full with unintelligible acronyms, tangles of cords and invisible wireless signals, means a breakdown is almost inevitable. The loss of a computer, cell phone or other gadget can be so jolting that it is fueling the rise of what some psychologists call “computer rage.”

The phenomenon is transforming the nature of technology service, an industry long infamous for being impersonal. Business is booming for companies with names like Rent-a-Geek, Geeks on Call and Geek Squad that make house calls to fix computers. Television technicians, once near extinction, are again driving to homes to adjust complicated settings on high-definition sets and hook them up to multi-component home-entertainment systems. Some of the world’s largest computer makers train their support personnel as much about customers’ delicate psyches as they do about technical matters. “There’s this frustration that you are really dependent on these things that you don’t understand and that you have no idea how to fix,” said Kent L. Norman, a researcher at the University of Maryland’s Laboratory for Automation Psychology and Decision Processes. “We place so much trust in computers that it gets a little scary.”

No one is immune. No device is exempt. Online message boards are filled with rants about iPods — sold by the millions on the idea that they are easy to use — freezing up, and $50,000 luxury cars with windows that roll up and down on their own at random times.

The recounting of one’s personal technological Armageddon is often desperate and emotional. A recent survey by Norman found that as many as one out of 10 users have hit, kicked or otherwise abused their equipment.

Barbara Gould said that in the past two years her family’s computers have broken down six times and her cell phone twice. Then, while she was in the middle of watching the “Lord of the Rings” trilogy one night, her DVD player mysteriously began to freeze every few minutes. “I was ready to throw everything out the window or burn them or do something violent,” said Gould, 53, a contractor for Fannie Mae, who works on manuals and other technical documentation.

Instead, Gould, who lives in Herndon, ran a search on Google and found Erik Bursch, a computer-repair consultant who works in the Tysons Corner area. Bursch said he has made several hundred house calls over the past few years and that he is often welcomed as a conquering hero. He said he has found more and more people willing to pay the $60 to $70 an hour he charges.

The peaceful, park-like setting of the DriveSavers compound in a San Francisco suburb belies the frenzy inside. The company’s labs operate like a hospital emergency room.

Chessen, 31, and the other 12 customer service representatives do triage. The challenge is to recognize which of the five stages of grief — denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance — a given customer is in, and respond accordingly. One recent afternoon, a man whose small business had burned down was telling Chessen how his insurance company was still inspecting the place so he could not even go in to see the carpets or to fetch his computer — on which he had a lot of important documents. “I was thinking, Why is he yelling at me?” Chessen said later.

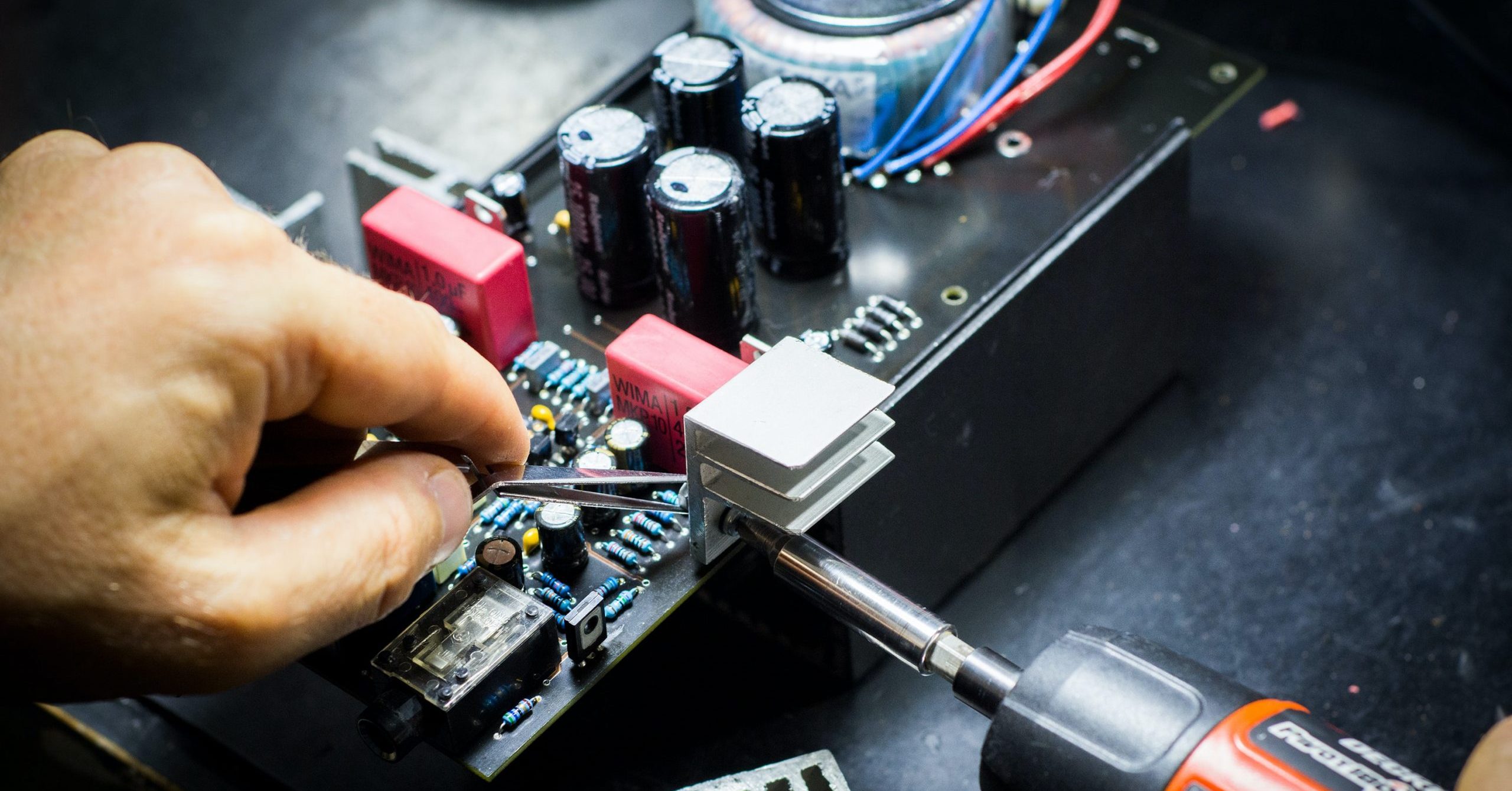

In another part of the building, delivery people rush in and out with oddly shaped cartons containing precious cargo. The contents of the boxes, hard drives and other data storage devices, are carefully taken to a clean room where they are dissected by technicians in white jumpsuits and blue gloves and then “cloned.” The copies are sent upstairs to data specialists who try to retrieve and reconstruct what people are looking for.

Sometimes the information is important only to the person it belongs to — pictures of one’s firstborn, musical compositions, r»sum»s, old e-mail, business plans, love letters. For others, it is something more: scripts for 12 then-unaired episodes of “The Simpsons”; research data for a cancer scientist at a major East Coast university.

The work is not cheap — the bill is usually $500 to $2,000 — but for many the information is priceless. In addition to paying the company’s fees, some customers have sent wine and roses to show their gratitude.

David K. Schoenkin, executive director and asset management consultant at Oppenheimer & Co., recently lost his computer, Palm Pilot and cell phone when he dropped his shoulder bag in a Manhattan street and an 18-wheeler ran over it. He said the crunch of the truck going over his equipment was “horrible, deafening” as he thought about losing his journals from five years of travel to Kenya, Morocco, Chile and Laos and digital pictures of the paintings he created and sold years ago when he was an art student. “You have to understand how devastating this was. Every single piece of electronic detail in my life was lost,” he said. DriveSavers managed to recover everything.

Not everyone is so fortunate. Ed Sit, the no-nonsense 49-year-old who is the clean-room manager, has the difficult job of giving people bad news. Some customers politely thank him for trying, Sit said. Others want to cast blame. They think that if they talk to his boss or if they pay more money they can get a different result. Sit said he thinks to himself: “I’m sorry — but if your relative is dead in a hospital, even millions and millions of dollars are just not going to bring him back.”

The loss of a computer, cell phone or other gadget can be so jolting that it is fueling the rise of what some psychologists call “computer rage.” The phenomenon is transforming the nature of technology service, an industry long infamous for being impersonal.

© 2005 The Washington Post Company